Maria Sibylla Merian

1647 – 1717

Maria Sibylla Merian

Entomologist

Scientific Illustrator

Ecological Pioneer

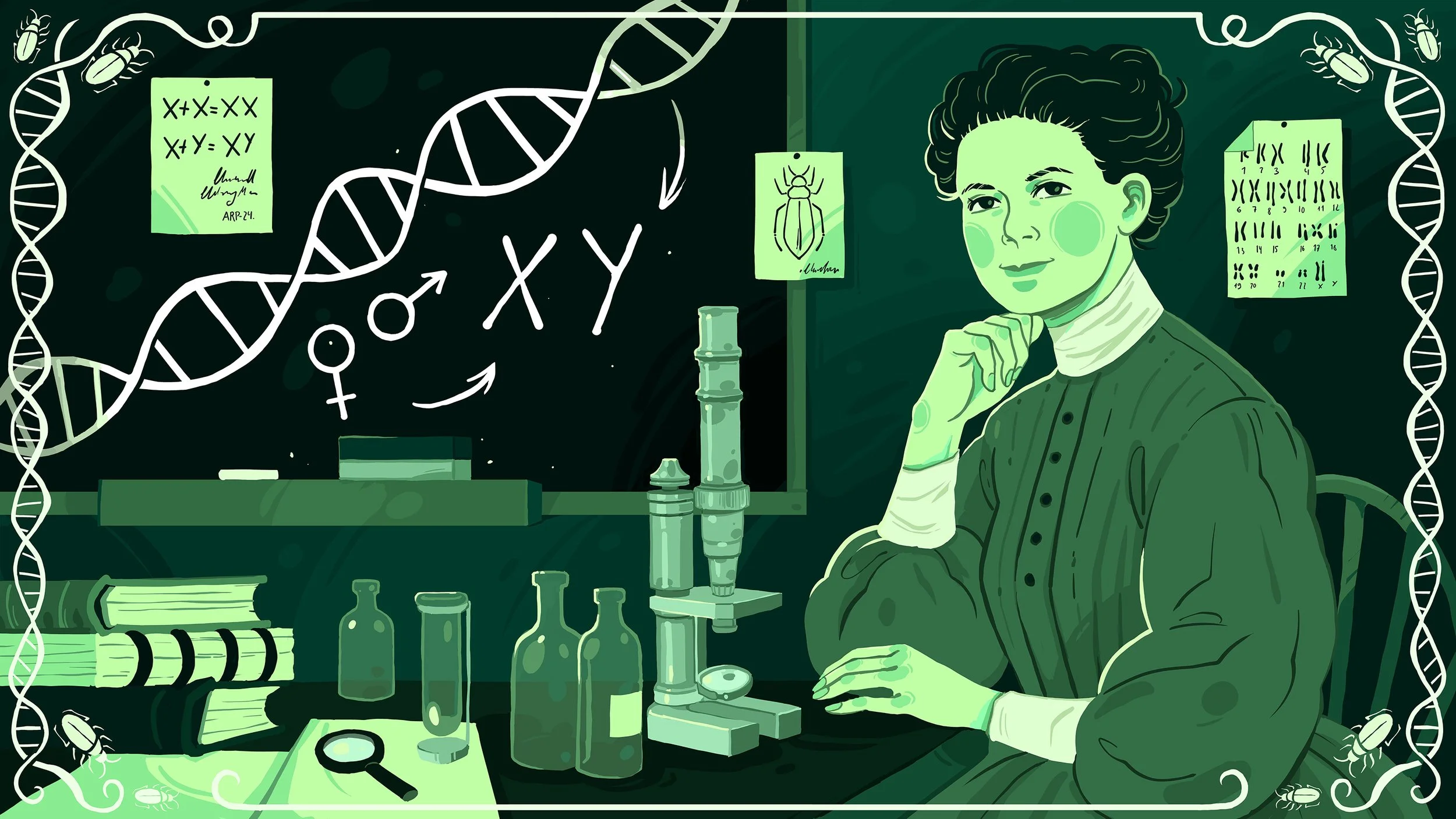

Portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian.

Origins in Ink and ImaginationMaria Sibylla Merian was born on April 2, 1647, in Frankfurt am Main, into a world steeped in print, pigment, and publishing. Her father, Matthäus Merian the Elder, was a Swiss-born engraver and publisher of international acclaim whose illustrated folios—among them Topographia Germaniae and the Theatrum Europaeum—helped define seventeenth-century visual culture. His passing when Maria was just three left a void quickly filled by the artistic legacy of her stepfather, Jacob Marrel, a still-life painter who raised her in a household where art was not only seen but lived.

From a young age, Merian was captivated not just by the objects in Marrel’s lush compositions—flowers, fruit, vines—but by the insects that hid among them. While others saw caterpillars as decorative flourishes, Merian saw creatures with stories to tell. At thirteen, she began raising silkworms, soon extending her curiosity to other larvae and their transformations.

This fascination would fuel a lifetime of inquiry, bridging the gap between aesthetic vision and empirical observation.

Imaginative illustration of Maria Sibylla Merian as a child, depicted at the scale of the insects and plants she would later study, symbolizing her early fascination with the natural world.

The Naturalist in the Drawing RoomIn 1665, Merian married Johann Andreas Graff, one of Marrel’s apprentices. Their move to Nuremberg marked the beginning of a productive chapter in her life. Between managing a household and raising two daughters, Johanna Helena and Dorothea Maria, Merian taught art to young women and began publishing a series of florilegiums—ornamental books of flower engravings designed for embroidery and painting. These early works, such as Neues Blumenbuch (1675–1680), showcased her technical prowess but hinted at deeper preoccupations. Even in these commercial prints, she began introducing insects with remarkable anatomical accuracy, positioning them not just as embellishments, but as ecological participants.

Illustration inspired by Maria Sibylla Merian’s 1679 publication Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandelung und sonderbare Blumen-nahrung (The Wondrous Transformation of Caterpillars and Their Remarkable Diet of Flowers), with insects and fruits surrounding the book to reflect its rich botanical and entomological content.

Her 1679 publication, Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandelung und sonderbare Blumen-nahrung (“The Wondrous Transformation of Caterpillars and Their Remarkable Diet of Flowers”), signalled her transition from decorative artist to scientific observer. Based on direct observation, each engraving depicted insects across multiple life stages—egg, larva, pupa, adult—alongside the specific plants they relied on for nourishment.

At a time when insects were still thought to spontaneously emerge from mud or decay, Merian’s observations contradicted centuries of Aristotelian dogma. Her work—grounded in patient rearing, detailed field notes, and visual analysis—positioned metamorphosis as a natural, observable process and opened new scientific pathways in entomology.

A Religious Detour and the Return to ScienceBy 1685, discontented with life in Nuremberg and estranged from her husband, Merian left the city with her daughters and mother to join a Labadist commune in Wiewert, Friesland. The Labadists, a radical Protestant sect led by the theologian Jean de Labadie, promoted simplicity, chastity, and piety. While Merian's artistic production dwindled during this time, her years among the Labadists appear to have deepened her spiritual outlook and perhaps solidified her belief that understanding nature was a form of devotion.

After her mother’s death in 1690, Merian left the commune and moved with her daughters to Amsterdam, then the epicentre of European trade, art, and scientific thought. There, she gained access to the private cabinets of curiosities maintained by wealthy patrons such as Nicolaas Witsen and Frederick Ruysch.

But it wasn’t enough to observe exotic specimens second-hand. Merian wanted to see nature in situ—to follow life not just in drawings or jars, but through its own temporal rhythms. In 1699, at the age of 52, she set sail for Suriname.

Illustrations by Maria Sibylla Merian from Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium. From left to right: Row 1 — Plates 22, 8, 6, 11; Row 2 — Plates 71, 45, 5, 49; Row 3 — Plates 18, 1, 4, 66; Row 4 — Plates 59, 15, 12, 2.

The Alchemy of Curiosity: A Journey to SurinameWhen Maria Sibylla Merian boarded a ship to Suriname in 1699, she wasn’t just breaking with social convention—she was shattering it. At 52, she left behind the safety of Amsterdam and sailed nearly 5,000 miles across the Atlantic with only her youngest daughter and a mission: to study the life cycles of insects in their native environment. She was neither sponsored by a royal society nor sent by a wealthy patron. This was not a gentleman’s expedition. This was something else entirely—a voyage of purpose, of passion, and of unrelenting scientific ambition.

Sequential illustrations of Maria Sibylla Merian engaging with the natural world: touching a pineapple, observing plants, and listening to an insect—echoing her vivid firsthand observations from her 1699 scientific voyage.

Amid the heat and thickets of the South American tropics, Merian encountered a world alive with colour, complexity, and contradiction. Her notes mention the stinging fibres of pineapples, the sharp scent of pepper plants, and the hum of wingbeats as moths emerged from their pupae. She captured the split tongues of sphinx moths, the precision of leafcutter ants, and—famously—a tarantula devouring a hummingbird. This last image shook 18th-century natural history to its core.

Her observations didn’t merely record nature; they reframed it. Gone were the sterile diagrams of insects floating on white pages. In their place, she presented dynamic tableaux—larvae munching leaves, butterflies in flight, predators and prey entangled in their ecological theatre.

Illustration inspired by Plate 18 from Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (1705), depicting a spider preying on a bird—a claim once mocked but confirmed two centuries later. Merian’s work shaped scientific illustration and influenced naturalists like Mark Catesby and Carl Linnaeus.

More than that, she listened. To enslaved people. To Indigenous knowledge-holders. To women whose botanical wisdom was passed orally and never printed. Her entry on the peacock flower—used by enslaved women as an abortifacient to deny their captors future generations—was more than botanical annotation. It was resistance rendered in Latin script.

Merian fell ill before she could complete her intended five-year stay. But her legacy—Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, published in 1705—would ignite imaginations across Europe. For the first time, flora and fauna were entangled on the page, just as they were in life.

Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium and a Legacy SealedUpon her return to Amsterdam in 1701, Merian began preparing what would become her magnum opus: Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (1705). A lavish folio of 60 hand-coloured engravings accompanied by detailed notes, the work was revolutionary. In contrast to the era’s taxonomic or diagrammatic norms, Merian depicted insects, plants, and animals together in vibrant, often dramatic ecological scenes. Spiders devoured hummingbirds. Leafcutter ants carried foliage to their subterranean nests. Frogs straddled branches, surrounded by their own offspring.

Bird’s-eye view illustration of Maria Sibylla Merian’s workspace, featuring open books, notes, ink, insects, and artistic tools she used to create her detailed natural history illustrations.

The book’s publication was self-financed—its copperplates etched by Merian herself, and the watercolours likely coloured by her daughters. Though some details were later critiqued—misclassifications, species mismatches—the essential insights held up. Henry Walter Bates, writing two centuries later, confirmed her once-mocked claim that spiders could prey on birds. Her artistic renderings helped establish standards for scientific illustration, influencing generations of naturalists, including Mark Catesby and Carl Linnaeus.

Yet in her lifetime and long after, Merian’s scientific authority was quietly undermined. She was often spoken of as a gifted painter rather than a serious observer of nature. As a woman in the early Enlightenment, she was not invited to scientific societies or permitted to publicly defend her own ideas—even when male naturalists debated them. After her death, prominent 19th-century English naturalists openly dismissed her methods, ridiculing her for deviating from conventional forms. The very qualities that distinguished her work—its integration of life cycles, habitats, and species interaction—were deemed “unscientific” by men who saw objectivity through a narrower, masculinized lens.

Her approach, which balanced observation with artistry, was quietly erased from the lineage of scientific illustration. For decades, she was either footnoted or forgotten. Even as Linnaeus incorporated her illustrations into his naming of species—some of which bear her name today—her intellectual contributions remained unacknowledged.

This silence was not incidental. It reflected deeper structures of erasure: a pattern where women’s ideas were absorbed into scientific canons without attribution, their labour aestheticized but their authorship ignored. Merian’s ecological sensibility, her capacity to see systems rather than specimens, was dismissed not for lack of merit but for lack of permission.

Her work endured—but her name did not.

Maternal Science and Artistic LineageMerian’s intellectual life was entwined with her daughters’. Both Johanna and Dorothea became accomplished artists and scientific illustrators, trained by their mother in both technique and inquiry. After Merian’s death in 1717, Dorothea moved to St. Petersburg, where she became the first woman appointed to the Russian Academy of Sciences. Johanna, having returned to Suriname with her husband in 1711, left behind a limited but remarkable body of work.

Merian’s maternal model of science—embodied by her intergenerational laboratory, her domestic observations, and her insistence on empirical care—challenges modern binaries between art and science, home and field, gender and knowledge.

The Veil of ForgettingFor all her acclaim during her lifetime, Maria Sibylla Merian’s legacy nearly vanished. By the dawn of the 19th century, she was remembered—if at all—as a decorative illustrator, her scientific contributions dismissed, her observations scrutinized or discredited. Her images had been misprinted, misattributed, or rendered so poorly that some began to question their accuracy altogether. Victorian ideals had no place for a woman who painted insects feasting on one another or rendered metamorphosis as a relentless, violent bloom.

Even her correct observations—like the bifurcated tongue of the sphinx moth or the bird-hunting tarantula—were challenged by male naturalists who declared them fanciful. Her work, which once sold for hundreds of guineas and hung in royal cabinets of curiosity, was shelved, forgotten, or absorbed anonymously into the lineage of scientific illustration.

It did not help that the language of her work—meticulous yet poetic—straddled the liminal space between art and science. She was neither fully accepted by the artists nor embraced by the scientists. She had forged a third path, and the world, for a time, failed to follow.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that scholars, historians, and feminists began to retrieve her from the footnotes. Paintings in the British Museum, long credited simply to “a Dutch school,” were reattributed. Her voice was recognized again in her writings—measured, reverent, fiercely observant.

In those lost centuries, the seeds she had planted—both literal and metaphorical—had waited, dormant, until the right conditions returned.

A Final MoultIn recent decades, Merian’s influence has begun to echo more loudly. Her botanical illustrations have resurfaced on German postage stamps, porcelain, and currency. Museums across Europe and North America have mounted exhibitions in her honour, including the Getty’s Maria Sibylla Merian & Daughters, which re-situated her within both artistic and scientific lineages. In 2018, a newly identified butterfly species—Catasticta sibyllae—was named for her, offering the kind of taxonomic recognition once denied in her lifetime. This renaissance is more than nostalgic recovery. It reflects a recalibration of whose observations are counted and whose hands get remembered. Merian’s afterlife is not merely celebratory—it is corrective. The overlooked are being re-centred, and the insects she so lovingly painted now carry not just ecological insight, but the mark of a woman who insisted on being seen (Mathrani, 2019).

It is perhaps fitting that the woman who taught Europe how to see metamorphosis underwent one of her own—posthumously. Today, Maria Sibylla Merian is heralded not just as a gifted illustrator but as a pioneer of behavioural ecology, a forerunner of entomology, and a radical documentarian of interconnected life. Scientists name species in her honour. Artists mimic her compositions. Feminist scholars trace her margins.

But more than any one discipline, Merian’s legacy resides in the way she looked at the world—with wonder sharpened by precision. She dared to study the overlooked, to centre insects and the hands that cared for them, to paint chewed leaves and parasites, to dissect pupae and sit through sleepless nights waiting for wings to unfurl. She elevated the lives of small creatures at a time when women’s own intellectual ambitions were similarly contained.

What makes Merian remarkable is not simply that she was ahead of her time, but that she made time—through sheer persistence—bend to meet her. She inhabited a space beyond taxonomy: one where the vibrancy of a caterpillar’s diet, the sorrow of an enslaved woman’s voice, and the mechanics of a chrysalis were all part of the same ecological truth. Her curiosity, exacting and ecstatic, never demanded separation between science and art, between beauty and brutality, between life and its constant unfolding.

Three centuries later, her images still breathe.

They crawl and molt and bloom.

And they remind us—just as she once did—that transformation, no matter how quiet or slow, is always in progress.

Illustration of a butterfly perched on an ink bottle, with a pen resting beside it — symbolizing the delicate intersection of nature and art in Merian’s work.

We have authored and illustrated this entry with care and respect, aiming to achieve the highest standards through diligent, balanced research. We also strive to maintain the highest standards of accuracy and fairness to ensure information is diligently researched and regularly updated. Please contact us should you have further perspectives or ideas to share on this article.

-

Akram, R. (2017, May 26). The woman who made science beautiful. Royal Botanic Gardens. https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/the-woman-who-made-science-beautiful

Art Herstory. (2021, January 26). Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology. https://artherstory.net/curiosity-and-the-caterpillar/

British Museum. (n.d.). Maria Sibylla Merian: Pioneering artist of flora and fauna. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/animals/maria-sibylla-merian-pioneering-artist-flora-and-fauna

Klein, J. (2017, January 23). A pioneering woman of science re-emerges after 300 years. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/23/science/maria-sibylla-merian-metamorphosis-insectorum-surinamensium.html

Mathrani, V. (2019, May 21). Maria Sibylla Merian: Botanical Illustrator, Entomologist, and Explorer Ahead of Her Time. UntoldStories.net. Retrieved from https://untoldstories.net/1667/04/maria-sibylla-merian-botanical-illustrator-entomologist-and-explorer-ahead-of-her-time/

Merian, M. S. (2016). Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium 1705. Lannoo.

Rogers, K. (2024, May 3). Maria Sibylla Merian. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Maria-Sibylla-Merian

Ruiz, P. (2024, March 6). Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (1705). The Public Domain Review. https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/merian-metamorphosis/

Schiebinger, L. (2005). Plants and empire: Colonial bioprospecting in the Atlantic world. Harvard University Press.

-

Website Name: The Matilda Project

Title of Entry: Maria Sibylla Merian

Author: Shehroze Saharan

Illustrator: Michelle Cheng

Editor: Mayoorey Murugathasan

Original Publication Date: September 06, 2025

Last Updated: September 06, 2025

Copyright: CC BY-NC-ND

Webpage Specific Tags: Maria Sibylla Merian; Naturalist and scientific illustrator; Entomology pioneer; Metamorphosis of insects; Botanical illustration; Women in science; Scientific exploration; Early female naturalist; Insects of Suriname; 17th-century scientist; Scientific expeditions; Insect life cycles; Art and science integration; German-born naturalist; Colonial scientific travel; Scientific illustration history; Contribution to entomology; Women in natural history; Enlightenment science; Early ecological observation; Observation-based science; Scientific legacy of women; Surinamese flora and fauna; Scientific documentation; Influence on Linnaeus; Early environmental awareness; Artistic precision in science; Advocacy for women in science; Intersection of art and biology; Female scientific pioneers; Early field biology.

Website Tags: The Matilda Project, The Matilda Effect; Margaret W. Rossiter; Matilda Joslyn Gage; Implicit bias; Unconscious bias; Gender attribution bias; Scientific recognition bias; Gender discrimination in academia; Stereotype threat; Pay gap in STEM; Glass ceiling in science; Sexism in scientific research; Gender stereotypes in education; Gender bias in peer review; Bias in STEM hiring practices; Impact of gender bias on scientific innovation; Underrecognition of female scientists; History of women in science; Women scientists in history; Notable women in science; Pioneering women scientists; Women Nobel laureates; Female role models in science; Gender disparities in scientific research; Women's suffrage movement; Historical women's rights leaders; Historian of science; STEM gender gap; Women in STEM; STEM education; Challenges faced by women in STEM; Representation of women in tech; Initiatives to support women in STEM; Gender equity in STEM education; Encouraging girls in STEM; STEM outreach programs; Diversity in STEM curriculum; Equity, Diversity, Inclusion; Equity in education and workplace; Diversity training; Inclusion strategies; Inclusive leadership; Gender equality; Racial equity; Pay equity and transparency; Representation in media.

-

APA Citation:

Saharan, S. K. (2025, September 06). Maria Sibylla Merian. The Matilda Project. www.thematildaproject.com/scientists/maria-sibylla-merian

Author

Shehroze Saharan

Senior Manager, Institutional AI Strategy Development and Support - Vice-President, Digital Transformation and Chief Information Officer at George Brown College

Shehroze Saharan is the Senior Manager, Institutional AI Strategy Development and Support at George Brown College, where he leads the development and implementation of a college-wide strategy for the ethical and strategic integration of artificial intelligence across academic and operational environments. His work spans AI research and policy, adoption support, employee training, and faculty engagement, while also advising senior leadership on aligning AI initiatives with the college’s broader digital transformation agenda.

Previously, Shehroze served as Educational Technology Developer at the University of Guelph, where he was the institution’s pedagogical lead on AI in Education (AIED). He is also the founder and leader of the Teaching with Artificial Intelligence Conference, now the largest AI in Education event in Canada.

Shehroze holds a Master of Information from the University of Toronto and a Bachelor of Science in Biomedical Science from the University of Guelph. He is currently completing his Ph.D. at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), University of Toronto, where his research explores Generative AI in curriculum and pedagogy.

Beyond his institutional role, Shehroze is the Managing Director and Co-Founder of The Matilda Project, an award-winning open educational initiative that highlights the contributions of historically overlooked women in science.

Illustrator