Nettie Stevens

1861 – 1912

Nettie Stevens

Geneticist

Sex Chromosomes

Mealworm Beetles

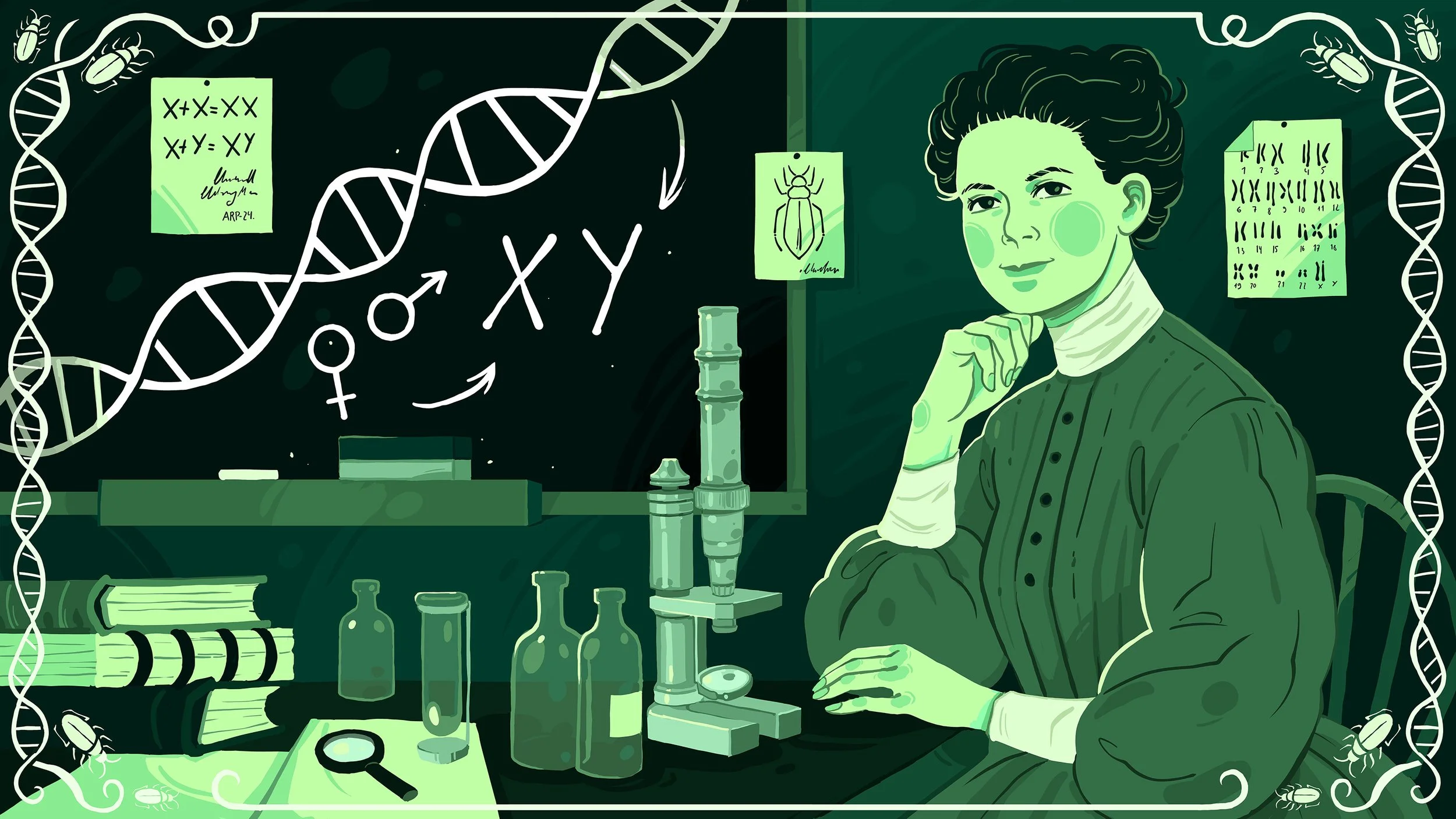

Portrait of Dr. Nettie Stevens.

Dr. Nettie Maria Stevens was a pioneering geneticist, researcher, and teacher who lived during the transformative period from the Civil War to World War One. During her teaching and research careers, she witnessed breakthroughs in science for women coinciding with the growth of her own field — genetics.

Early Life and Academic SuccessBorn in 1861, Stevens spent her early years in Cavendish and West Haven, Vermont with her family where her schooling began at the Forge Village Grammar School. Tragically, during her early life, Stevens faced the loss of three brothers and her mother, which marked the end of the family settlement in Vermont.

After the passing of her mother, Stevens’ family moved to Westford, Massachusetts where she attended secondary school at Westford Academy. While there, she developed a strong foundation in math and science. At a time when it was unusual for women to pursue education beyond grammar school, Stevens graduated from Westford in 1880 with high honours and near-perfect grades in all subjects.

While Stevens and her sister Emma both shared a passion for science and scholarship, only Stevens went on to pursue advanced studies.

Despite the prevailing norm that discouraged women from seeking education beyond Grammar School, Stevens defied conventions and enrolled at Westford Academy, where she cultivated a strong foundation in mathematics and science.

Teacher to ResearcherStevens’ teaching career began at a high school in Lebanon, New Hampshire, where she taught Latin, English, physiology, zoology, and mathematics. However, she only remained there for a short time before pursuing advanced education at Westfield State Normal School, a teacher’s college (now Westfield State University). Her dedication to her studies was evident in her perfect attendance records and achievement of the highest entrance examination scores. Her lowest score was 95% in arithmetic. Stevens completed a four-year program in only two years with the principal noting that this was a feat only a genius could demonstrate. Stevens returned to Westford Academy as a teacher in 1884.

At the age of 35, Stevens transitioned from teaching to research in the male-dominated field of genetics. She moved to Stanford University in 1896, marking the beginning of a new chapter in her life. Stevens’ academic ambitions extended beyond traditional gender roles. Despite societal norms and limited opportunities for women, Stevens overcame obstacles to pursue higher education and a career in genetics.

Ground-breaking Research at Stanford, Bryn Mawr College, and BeyondAt Stanford, Stevens studied under Frank Mace MacFarland and spent four summers studying at the Hopkins Marine Station in the Seaside Laboratory where she focused on histology and cytology. By 1899, she had achieved enough credits to earn her A.B. degree (known today as a Bachelor of Arts). Stevens remained at Stanford to pursue her M.A. and published her first paper from her thesis.

In 1901, at the age of 39, Stevens began her Ph.D. at Bryn Mawr College bringing with her a graduate scholarship in biology. She worked under notable scientist Thomas Hunt Morgan and after six short months at Stanford, she earned a fellowship to conduct research abroad. Her work in Italy and Germany contributed to her Ph.D. project and she completed her degree in 1903, after just two years.

In 1912, Morgan noted, “it is rare for one who starts so late in life to attain in a few years so high a rank amongst the leaders in one's chosen field.” He attributed her success to her ability and devotion, as well as the progressiveness of Bryn Mawr College.

After graduation, she applied for a research assistantship from the Carnegie Institute of Washington to continue her work at Bryn Mawr. In her initial application, she shared that while she preferred research to teaching, she had hoped to obtain a teaching position, because it would be more financially lucrative and she had to support herself. However, there were very few teaching positions for women in biology that year. Stevens was not successful in her first attempt applying, but in her second attempt, which was supported by recommendations from Morgan, Edmund B. Wilson, Morgan’s former colleague M. Carey Thompson, the president of Bryn Mawr, and others, she was awarded a fellowship to continue her work at Bryn Mawr.

Stevens’ greatest discoveries occurred at Bryn Mawr following the completion of her Ph.D. Her observations and deductions about the different classes of sperm produced by male insect species, carrying either X or Y chromosomes, contributed significantly to the understanding of sex determination.

Stevens was the first to validate the hypothesis that there are two classes of reproductive cells (spermatozoa) in male mealworm beetles. Her observations and deductions, particularly regarding the distinct sperm classes carrying either X or Y chromosomes, significantly advanced our understanding of sex determination in insects.

In 1905, Stevens was the first to validate the hypothesis that there are two classes of reproductive cells (spermatozoa) in male mealworm beetles: ones with a large chromosome (later named the X chromosome) and ones with a smaller chromosome (later named the Y chromosome) and that females only made reproductive cells with a large chromosome (X).

While Edmund Wilson made a similar discovery around the same time, resulting in them being acknowledged today as co-discoverers, in 1978 Brush noted that she had arrived at a more correct hypothesis than Wilson. She correctly inferred how sex was determined in mealworm beetle offspring. Specifically, she inferred that because all unfertilized eggs from the female have the same chromosomal content (large), while spermatozoon from the males contained two classes (large or small), a female offspring results when an egg is fertilized by a spermatozoon with the large (X) chromosome, and a male offspring result when an egg is fertilized by a spermatozoon with the small (Y) chromosome.

With this evidence, Stevens concluded that biological sex is inherited as a chromosomal factor, that it is determined by a specific chromosome, and that males determine the sex of the offspring. Stevens was responsible for the groundbreaking discovery of linking X and Y chromosomes to sex determination, which was the “culmination of more than two thousand years of speculation and experiment on how an animal, plant, or human becomes male or female” (Brush, 1978). This discovery not only marked a significant milestone in unravelling the genetic foundations of sex but also laid the groundwork for subsequent breakthroughs. It has left an indelible impact on research, shaping the landscape of biology and contributing to our comprehension of sex-linked hereditary diseases.

For the following six years, Stevens proceeded to study the subject of chromosomal sex determination in more than fifty insect species, including aphids. In 1912 Morgan noted,

In 1905, Stevens won the Ellen Richards Prize, an award intended to promote scientific research by women, for her paper on the germ cells of two aphid species.

However, Stevens was not immediately recognized for her discovery on sex determination. For example, Morgan and Wilson were invited to speak at a conference to present their theories on sex determination in 1906, while Stevens was not invited to speak. This is despite the fact that Wilson acknowledged that Stevens had independently determined that the male mealworm beetle possesses dimorphism in spermatozoa before he had demonstrated it in other species in his paper published in December 1905. Even at the time of her death, Stevens’ discovery was still not widely accepted.

The Trustees of Bryn Mawr finally created a research professorship for Stevens, but she was never able to fill the position. Shortly afterward, Stevens’ life was tragically cut short by breast cancer in 1912 at the age of 50. Despite the brevity of her career, Stevens contributed more to the field of genetics than many scientists with life-long careers. With at least 38 publications, Stevens was one of the first and few American women to be recognized for her contributions to scientific research at that time.

While at Stanford and Bryn Mawr, Stevens faced the societal challenges of being a woman in science during a time when women were just starting to break through in science, and more specifically, the field of genetics. Despite this, Dr. Nettie Maria Stevens left an indelible mark on the field of genetics, paving the way for future generations of women in science.

Posthumously, Stevens was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1994, and on May 5, 2017, Westfield State University honoured Stevens by naming the Dr. Nettie Stevens Science and Innovation Center.

Mealworm Beetles (Tenebrio molitor).

The Matilda EffectWhile Stevens made groundbreaking contributions to the field of genetics, the Matilda Effect, a gender bias in the recognition of women's scientific achievements, impacted her legacy. Despite her significant role in discovering sex determination through chromosomes, Stevens’ work was not always given the recognition it deserved during her lifetime, nor was she granted the title of her achievement in a posthumous recollection of her life’s work.

Stevens' 1905 discovery, differentiating the role of X and Y chromosomes in sex determination, was pivotal for genetics. By establishing that females possess two X chromosomes (XX) and males have one X and one Y chromosome (XY), her findings provided a crucial framework for understanding the genetic underpinnings of sex, influencing subsequent research and shaping the field of biology.

At the time of Stevens’ discovery, Wilson had made more substantial general contributions to the field of genetics, which led to her hypothesis being credited to him. Additionally, Morgan’s contributions to the history of genetics have been considered more spectacular, resulting in him being wrongly credited for proposing the theory in many educational resources. The miscrediting of Stevens’ work is reflective of the broader challenges women scientists faced in receiving due credit for their work and highlights the pervasive gender biases that obscured Stevens' significant impact on the field of genetics.

Additionally, in the article written by Morgan on her scientific work and contributions, Stevens was not given the title of her highest academic achievement, Ph.D. In the article title and within the body of the work, Morgan repeatedly refers to Stevens with the title of “Miss,” while Wilson is honoured with the title of “Professor.” However, in the obituary Morgan penned for Wilson after his passing in 1939, he did recognize Stevens with the deserved title of “Dr.”

Despite the impacts of the Matilda Effect on the recognition of Stevens’ discoveries, Dr. Nettie Stevens was no doubt a key contributor to unravelling the mysteries of cytology and heredity. Stevens’ research in genetics has earned her a place of honour in the world of science.

We have authored and illustrated this entry with care and respect, aiming to achieve the highest standards through diligent, balanced research. We also strive to maintain the highest standards of accuracy and fairness to ensure information is diligently researched and regularly updated. Please contact us should you have further perspectives or ideas to share on this article.

-

Brush, S. G. (1978). Nettie M. Stevens and the discovery of sex determination by chromosomes. Isis, 69(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1086/352001

Choquette, C. J. (2022, September 15). The Story of Nettie Maria Stevens [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FnnummjoFBQ

Miko, I., & LeJeune, L. (Eds.). (2009). Essentials of Genetics. Cambridge, MA: NPG Education. https://www.nature.com/scitable/ebooks/essentials-of-genetics-8/135498091/

Morgan, T. H. (1912). The scientific work of Miss N. M. Stevens. Science, 36(928), 468–470. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.36.928.468

National Women’s Hall of Fame. (2024). Nettie Stevens. https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/nettie-stevens/

Ogilvie, M. B., & Choquette, C. J. (1981). Nettie Maria Stevens (1861-1912): Her Life and Contributions to Cytogenetics. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 125(4), 292–311. http://www.jstor.org/stable/986332

Stevens, N. M. (1906a). A comparative study of the heterochromosomes in certain species of Coleoptera, Hemiptera, and Lepidoptera, with especial reference to sex determination. Carnegie Institution for Washington.

Stevens, N. M. (1906b). Studies in spermatogenesis: With Especial reference to the “accessory chromosome.” Carnegie Institution for Washington.

Stevens, N. M. (1906c). Studies on the germ cells of aphids. Carnegie Institution for Washington.

Tricia, O. (2017, May 5). Westfield State celebrates opening of the Dr. Nettie Maria Stevens Science and Innovation Center. Westfield State University. https://web.archive.org/web/20180814201005/http://www.westfield.ma.edu/news/view/westfield-state-celebrates-opening-of-the-dr.-nettie-maria-stevens-science

-

Website Name: The Matilda Project

Title of Entry: Nettie Stevens

Author Christie Stewart

Illustrator: Alba Real

Editors: Sandy Marshall & Shehroze Saharan

Original Publication Date: February 16, 2024

Last Updated: March 31, 2024

Copyright: CC BY-NC-ND

Webpage Specific Tags: Nettie Stevens; Geneticist; Chromosome theory of inheritance; XY sex-determination system; Early American women scientists; Bryn Mawr College; Thomas Hunt Morgan; Sex chromosomes; Heredity and sex; Drosophila melanogaster; Female scientist pioneers; 20th-century genetics; Contributions to cytogenetics; Female role models in science; Gender barriers in early science; Historical women in STEM; Chromosomal basis of inheritance; Women's contributions to biology; Legacy in genetics; Pioneer in sex determination research.

Website Tags: The Matilda Project, The Matilda Effect; Margaret W. Rossiter; Matilda Joslyn Gage; Implicit bias; Unconscious bias; Gender attribution bias; Scientific recognition bias; Gender discrimination in academia; Stereotype threat; Pay gap in STEM; Glass ceiling in science; Sexism in scientific research; Gender stereotypes in education; Gender bias in peer review; Bias in STEM hiring practices; Impact of gender bias on scientific innovation; Underrecognition of female scientists; History of women in science; Women scientists in history; Notable women in science; Pioneering women scientists; Women Nobel laureates; Female role models in science; Gender disparities in scientific research; Women's suffrage movement; Historical women's rights leaders; Historian of science; STEM gender gap; Women in STEM; STEM education; Challenges faced by women in STEM; Representation of women in tech; Initiatives to support women in STEM; Gender equity in STEM education; Encouraging girls in STEM; STEM outreach programs; Diversity in STEM curriculum; Equity, Diversity, Inclusion; Equity in education and workplace; Diversity training; Inclusion strategies; Inclusive leadership; Gender equality; Racial equity; Pay equity and transparency; Representation in media.

-

APA Citation

Stewart, S. (2024, March 31). Nettie Stevens. The Matilda Project. https://www.thematildaproject.com/scientists/nettie-stevens

Author

Dr. Christie Stewart

Associate Director (Acting) - Office of Teaching and Learning at the University of Guelph

Dr. Christie Stewart’s professional journey is marked by a breadth of experiences. She currently focuses on faculty development and the advancement of institutional teaching and learning initiatives as the Associate Director (Acting) in the Office of Teaching and Learning at the University of Guelph. Her expertise also extends to workshop design and facilitation covering a breadth of topics tailored for both faculty and graduate students. Before stepping into her current role, she made significant contributions at St. Clair College and the University of Windsor as an Educational Developer. There, she guided faculty members through the intricacies of learning outcomes, assessment alignment, and course and curriculum design. Christie's instructional journey spans more than a decade, during which she held positions as an Assistant Professor, Instructor and Academic Advisor. Her teaching has impacted thousands of students in the fields of Environmental Science and Biology at several Canadian institutions, namely Western University, Huron University College, and St. Clair College.

Illustrator